Rathlin O'Beirne lighthouse and keepers' cottages (photo by Karl Birrell)

With the exception of the uncategorisable Kish light, you can probably divide Ireland's coastal lighthouses into three main categories - onshore lighthouses, island lighthouses and rock lighthouses, where the difference between the latter two would be that rock lighthouses had no other inhabitants. And, in general (again) it was on the rock lighthouses that most of the dramas occurred. The histories of the Tuskar, Fastnet, Slyne Head etc are littered with shipwrecks and drownings and shaking towers and tenders capsizing and make for stirring reading.

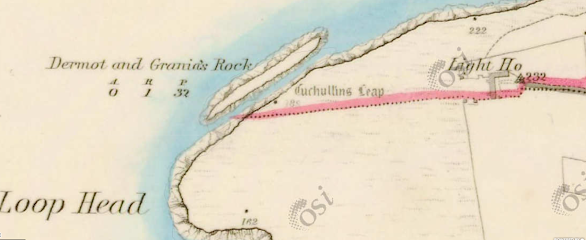

Alone among the west coast rock lights, Rathlin O'Beirne, off the coast of south west Donegal (and not to be confused with Rathlin Island on the north coast) seems to have led a beatific, serene existence, compared to its wave-lashed neighbours. Of course, it is larger (only slightly moreso than the Skelligs) but it is not far from Eagle Island and Blackrock Mayo yet, unlike them, reliefs were seldom long delayed.

In case anyone feels I am labelling R.O'B 'boring,' I should point out that, in operating a lighthouse on that coast for 160 years with only one relatively minor accident, this unheralded light station, its keepers and boatmen, deserves to be feted as one of the most successful stations in the country.

Of course, the day I visited was hazy in sharp comparison to the other radiant photographs on this page! This photo taken from the mainland in September 2021

Asicus the Gaul was a religious bigwig in the late 400s. He was Abbot-Bishop of Elphin and later of Ireland and had performed the last rites on St. Patrick, hopefully when the latter was on his death-bed. However, somebody told a dirty rotten fib about him and he stomped off, first to the top of Sliabh Liag and then (finding that too congested?) to the desert island of Rathlin O'Beirne, where he established a hermitage. The place has been a pilgrimage destination ever since.

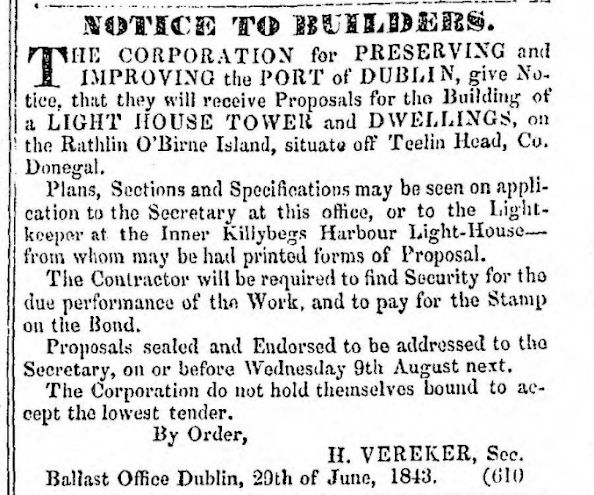

It was in 1841 that the shipowners of Sligo called for a light to be erected on the northern point of Sligo Bay and only a further two years before building was due to start : -

However, the hold-ups were many and frequent, mostly due to litigation. It was not until 14th April 1856 that the catadioptric flashing light first shone forth.

This was altered to a fixed light on 1st June 1864 and the old (?) lighting apparatus moved up to Arranmore Island. This lasted until 1st June 1893 when the light was changed back to 'flashing.' Now let's see who calls it a boring lighthouse.

The island is around 3kms from the harbour at Malin Beg and comprises roughly 50 acres

In 1902, as rock stations around the country were slowly being made relieving, a question was asked in the House of Commons about the educational and spiritual needs of the children of the keepers on the island: -

In fact, it was not until 1912 that the poor pagan, uneducated lightkeeping kids were dragged, kicking and screaming onto the mainland to avail of the four sturdy houses at Gannew, Glencolmcille. These houses served Irish Lights for 45 years until they were sold off to a Mr. and Mrs. Markey of New York in 1957.

The lightkeepers' cottages, front and rear, in September 2021

I mentioned one minor accident on the island - well, not minor to the victim - and this occurred in 1940: -

In 1974, Rathlin O'Beirne became the first and only lighthouse to be powered by nuclear energy with a big dollop of Strontium 90 used to keep the light going. Surprisingly, this only lasted for 13 years when the light was found to have become rather feeble. The nuclear age then became the wind age with a wind turbine producing the energy to run the light. In 1994, it became the first major Irish lighthouse to be run on solar power.

The lighthouse in 1905, photo taken on an Irish Lights inspection trip, photo in the National Library of Ireland

The lighthouse keepers' cottages on the island. In 2019, the whole island (minus the lighthouse itself) went up for sale. The estate agents thoughtfully provided a million photographs, which can be found here

The extremely safe boat tender to and from the island was for most of the lighthouse's history in the domain of the Jones family of Malin Beg. Edward Jones was succeeded in his duties by his son, Michael. Michael's duties were eventually taken over in turn by his three sons, Edward, Michael and Thomas, together with a nephew. A fourth generation Jones, Michael, became the attendant when the lighthouse was automated in 1974. One can just picture Michael at his hall door, "I'm just going to brave those vicious currents in my flimsy boat to check the nuclear reactor on the island, love...."

The boat generally landed on the sheltered eastern side of the island at a small pier, from which stone steps lead up to an incredible walkway, flanked by two very long 8 feet high stone walls to shelter the keepers on the journey to the lighthouse on the west side of the island and to protect them from the savage black-faced sheep which today are the island's only sizable inhabitants.

Photograph by Michael Hegarty

Without access to the Irish Lights archive, these are but a few of the keepers who have lit this very safe and definitely not boring light down through the years: -

In 1869, William Duffy and Owen McClosky both contributed to the subscription for the drowned Calf Rock boatmen.

In 1871, the keepers were Michael Brownell, PK, and Owen McCloskey, AK.

In October 1876, Bridget Gillespie, wife of keeper George, gave birth to twin sons John and Neal, surely the only twins to be born on the island.

The 1901 Census lists George James and Richard Hamilton as lightkeepers on the island.

The 1911 Census shows John J. Gillespie, Thomas Jones and Thomas F. Ryan to be the lightkeepers. John Gillespie's age means he is more than likely one of the 1876 twins.

Keeper Charles Loughrey's wife, Lucy, died at Glencolmcille in 1916.

Walter Coupe, AK, left the island after three years in 1938.

His replacement, Francis S. Ryan was the son of F. Ryan who was PK for 'a long number of years' (probably the Thomas F. Ryan on the 1911 Census)

John Corish, AK, also left the station in 1938.

James McGinley was the PK in August 1939.

'Con Murrin,' AK, could not attend his father's funeral due to heavy seas in 1940. Another newspaper report names him as Cornelius Meenan. The minor incident above also references 'Con Meenan.'

Frederick James, keeper, married Ms Louie Maxwell at Glencolmcille in January 1941.

Charles McNelis, PK, retired in October 1942 after 35 years in Irish Lights.

M. Murphy was transferred to R. O'B in March 1951. He had served at the station 'about 13 years previously.'

He replaced Michael O'Boyle who was transferred to Fanad.

In June 1951, AK Patrick Brennan was transferred to Inisheer. His replacement was T. Shanaghan.

In the same month, Charles Hernan was transferred to Inishowen.

His replacement was Frederick James, who had previously served at the station 'for a term.'

In September 1954, Michael Jones AK, was transferred to Rockabill.

PK David Murphy, who had been at R O'B since 1951 died at his lodgings at Glencolmcille in September 1956.

Martin Kennedy, AK, was transferred on promotion to Galley Head in October 1956.

In December 1960, wonderful boatmanship by Edward Jones meant that PK Campbell could be relieved for Christmas by AK Kane.

Reggie Hamilton also served at Rathlin O'Beirne around this time.

The last keepers before automation in 1974 were PK Brendan McMahon and AKs Thomas Roddy, Hugh Sullivan and A.J. Cronin.

It is a sobering thought that in January 1975 - shortly after the last keepers left the island - six men lost their lives when the MFV Evelyn Marie foundered on a reef off Rathlin O'Beirne. They were Paddy Bonner, Hugh Gallagher, Johnny O’Donnell, Roland Faughnan, Tom Ham and Joe O’Donnell.

Incredibly, the following year the MFV Carraig Una went down on the very same reef and five men - Ted Carbery, John Boyle, Anthony McLaughlin, Michael Coyle and Doalty O’Donnell - were drowned.

Among the many unanswered questions about the terrible loss of life in the two incidents, there also remains the nagging thought that, had the lighthouse been manned, assistance might have been summoned much quicker and some of the victims may have been saved.