The short career of lightkeeper Edward Doran

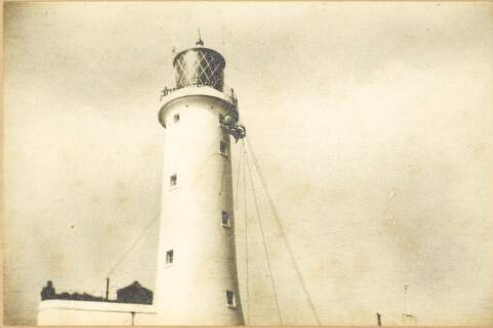

The East Twin light 1946. The house was built in 1925, shortly after the events in this post. The original light was a large triangle. Many lighthouse enthusiasts will be familiar with the IRA raids on Irish lighthouses in the late 1910s / early 1920s. Remote and difficult to protect, light stations such as Mine Head, Roancarrig, Hook and even the Fastnet, were raided by Republicans. They were mainly interested in the gun cotton which was used to fire the fog cannons but they wouldn't turn up their noses to personal hand guns and rifles, binoculars, telescopes etc. Such was the regularity of these raids, that the lighthouses had to withdraw their fog signalling service until normality was resumed. One armed, sectarian raid on a lighthouse, though, did not fit into the above template. Redmond 'Edward' Doran was a Catholic and keeper of the two East Twin lighthouses in Belfast Harbour. In one of the houses, he resided and the other it was his duty to maintain. Although boa...