Merry Christmas!

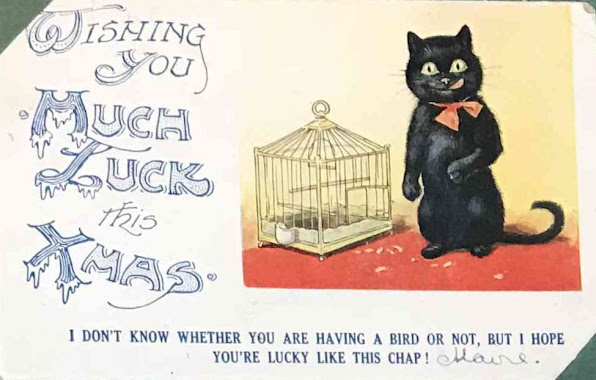

My posting has been fairly non-existent for December so as an apology, I wish you all a very merry Christmas and send you this very old Christmas card which seems to encapsulate what the festive season is all about. Imagine the eight-year-old child coming down on Christmas morning to find the cat has eaten her pet budgie .... I had hoped, as this is a lighthouse blog, to bring you a lighthouse Christmas card but they are few and far between and rarely very humorous. But there is a lighthouse link in the above card. Audrey Arthure is a fellow Irish lighthouse enthusiast and well she should be, as her pedigree of Hills and Whelans goes back to the first half of the nineteenth century, many of each family serving as either lightkeepers or coastguards. John Whelan, for example, joined the Ballast Board, (as was) in 1856/7, as the son of a lightkeeper. Frank Hill, born 1878 was both the son and grandson of a coastguard. Frank Hill and Annie Sweeney on their wedding day in 1908. Annie...