Knives out at Killybegs

St. John, in his lifetime, made many fine points but his best two were probably this lighthouse in Donegal and the wasp lighthouse in county Down

I am very grateful to the Great Lighthouses of Ireland site for this snippet of information concerning the tragic events of late 1886 in south Donegal. The site says the details were unearthed by the archivist at Irish Lights, a tantalising titbit that is hopefully the precursor of things to come, though hopefully not quite so traumatic.

It has always been a source of bewilderment to me why the naming of light stations around our coasts should be a cause of confusion. If there is a Blackrock lighthouse at Sligo, why name a subsequent lighthouse Blackrock, Mayo? Call it Mayo West or Belmullet Rock or something to avoid any vestige of possible confusion. In the trade, Crookhaven light and the Eeragh light are distinguishable both visually and geographically. Yet Irish Lights insisted on calling them both 'Rock Island.' And of course there are Black Head lighthouses in both Antrim and Clare.

(Incidentally, I see in a recent post by the Irish Lights archivists on St. Elmo's Fire, that they manage to confuse 'North Aran' - ie Eeragh - with Arranmore lighthouse. And before I pour scorn, I have many times confused Newcastle, county Down - coastal town in Dundrum Bay that once housed a lighthouse - with, erm, Newcastle, county Down, shore lodgings for the South Rock lightkeepers and lightshipmen.)

Of course, its not easy being in charge of naming things (ask my son, Adolf). When St. John's Point lighthouse in county Donegal was established in 1831, it was the only St. John's Point. How were the authorities to know that, thirteen years later, another St. John's Point lighthouse would be erected in county Down?

In between these two events, in 1838, a beautiful harbour light was established on Rotten Island, just outside of Killybegs port. This light was given the name 'Killybegs Harbour.'

So, they had 'St. John's Point' and they had 'Killybegs Harbour', in sight of one another. No problem there. Then along comes St. John's Point in county Down, bold as brass, in 1844 and the authorities have a problem. Two lighthouses both called St. John's Point? How were they going to rectify this?

The ingenious solution, which must have taken nights and nights of pacing up and down the Ballast Board offices in Westmoreland Street, was to re-name the original St. John's Point, 'Killybegs.' Brilliant! What could possibly go wrong? Unfortunately, for one Principal Keeper, forty years later, the confusion over nomenclature was to have serious consequences....

The keepers' cottages at St. John's Point, county Donegal, now holiday cottages for rent

On 1st December 1886, PK Joseph Hill of St. John's Point, Donegal, wrote an anguished letter to Head Office in Dublin, advising them that the return of three knives and forks, promised by the Commissioner of Irish Lights, had not yet materialised. The use of the word 'return' implies that the cutlery in question had in fact originated in Donegal and had been sent to Head Office for a reason. Maybe the bigwigs were having a function and were requisitioning knives and forks from around the country?

As a result of this shortfall, Mr. Hill goes on to state, he has "had to lend some of mine to the assistant," probably because he couldn't bear to watch the poor chap shovelling his dinner into his mouth with his big mutton hands.

This brief, pitiful letter sums up the hardship of life in remote stations, with not a hardware shop nearer than Dunkineely. (Incidentally, the letter was received in Dublin the following day, which is quite a salient comment on the state of our present-day postal service)

Joseph had joined the lighthouse service as a 23 year old in 1863 and had a wealth of experience. Son of a naval officer, he had married while stationed at Drogheda East and West lights on the Boyne Estuary. Four years later he was to be found keeping the light at the wild and remote Kingstown East light, the silence disturbed only by the whirling gulls and the thousands of walkers who thronged the pier every day. He did a turn on the Fastnet and then headed up to Rathlin O'Beirne light at the northern end of Donegal Bay. When he left there, his unpaid job of ornithologist, and paid job of lightkeeping, was taken over by one John Scallan.

After a stint on Oyster Island, managing one of the two lighthouses there, he was back up the coast again to St. John's Point (or, more correctly, Killybegs) and in the thick of the Great Cutlery Crisis, as it came to be known.

Christmas 1886 must have been a grim time at the lighthouse. Joseph and his family and the assistant, marital status unknown, must have sat around the cheerless table, waiting for others to finish before the knife and fork became available, doubtless cursing Santa for leaving their stockings cutleryless.

But their long and terrible ordeal finally was over on the last day of the year, when Joseph and one W. Rooney (hopefully Wayne, but probably William or Walter) scrawled a joyous and relieved note (from "Killybegs Lighthouse") back to Irish Lights informing them, somewhat ambiguously that "the six knives and forks have arrived."

But their long and terrible ordeal finally was over on the last day of the year, when Joseph and one W. Rooney (hopefully Wayne, but probably William or Walter) scrawled a joyous and relieved note (from "Killybegs Lighthouse") back to Irish Lights informing them, somewhat ambiguously that "the six knives and forks have arrived."

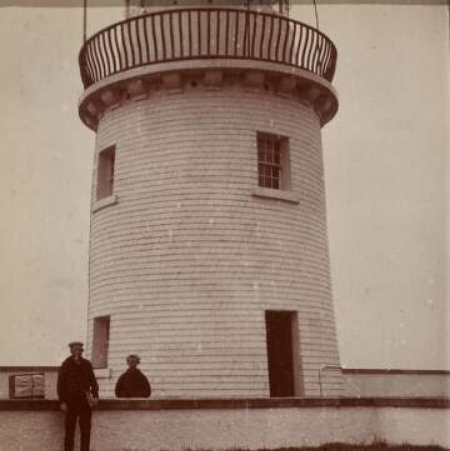

The lighthouse c.1903 (CIL photo in the National Library of Ireland)

But what had gone wrong? The Government set up a tribunal and sent down social workers to the lighthouse staff at St. John's Point but the recovering keepers said they could not get full closure until the facts of the matter came to light. But there was no clue as to the cause of the non-arrival of the promised cutlery.

Until that is, the 24th January 1887, when Irish Lights received a letter from "Killybegs Harbour Lighthouse" (ie Rotten Island).

"Having received a letter from Mr. C. Rodgers, Postmaster, Killybegs, pertaining to small parcel received containing 3 knives and 3 forks, which I received per parcel post in November, directed to this station.

'I respectfully ask, what am I to do with them, as I am not aware what station they belong to, as I am informed they belong to St. John's Point, Donegal." (great sentence by the way)

The letter was signed 'John Scallan,' the very same keeper who had taken over from Joseph Hill at Rathlin O'Beirne in 1883, and where he had remained at least until 1885.

The headlines reached right around the world. "Knives and forks discovered! President informed!" shouted the New York Post. "Cutlery mystery solved!" yelled the Sydney Morning Post. "Forkin hell!" screamed the Sun. Newspapers could be very noisy when they got excited.

Sadly, we are not privy to the reply from Irish Lights, who had obviously sent a replacement set out to St. John's Point. Did they instruct John Scallan to send them on to St. John's Point, running the risk of leaving the keepers there up to their eyes in cutlery? Did they tell Mr. Scallan to keep them and deduct the cost out of his salary? Or did they look for them back, as Mickser in Accounts was leaving and they were trying to organise another do?

We may never know.

In 1892, Joseph Hill was in charge of the very pretty lighthouse at Howth Harbour and when he retired, he lived in a house near the harbour, where he doubtless regaled the grandchildren with the story of 'how the knives and forks got lost,' if he could bring himself to put the episode into words. He died in 1913.

Post script: To counteract my flippant smart-arsery in relating the above tale, two points should be raised.

1) At the time that the keepers were complaining about the lack of cutlery, many of the people around St. John's Point, Inver, Killaghtee and Bruckless had precious little use for knives and forks. Hunger and deprivation didn't stop at the end of the famine and severe want, deprivation, malnutrition, evictions and even starvation were common in this part of Donegal in the 1880s.

2) Poor John Scallan, a married man, failed to see the end of 1887. He suffered a bad accident on Rotten Island in November 1887, fractured the base of his skull and died twelve hours later. He was 55 years old. I have no further details and would welcome any information on the cause of his accident.

Comments

Post a Comment