This weekend, I was booked in to go to Cross Island, one of the Copeland Islands. It's the island that had the lighthouses before Mew Island light was established in 1884 and is now run by the RSPCB and I was doing a 48 hour stint there. Unfortunately, someone called Betty kicked up a storm, and the boat was cancelled.

So, with a couple of days free, I used one of them to head down to the Shannon Estuary and took a tour of the lighthouse at Loop Head. And there I came across an interesting tale about which I'd never heard.

Loop Head is a corruption of Leap Head. There are a lot of Leaps in Ireland from Priests Leap on the Cork / Kerry border to Leixlip in co. Kildare. And of course Leap itself, also in Cork. They all have legends associated with them, all of which are highly improbable.

If you've ever been to Loop Head, you'll have obviously noticed the long, skinny rock lying parallel to the coast at the very end of the Head itself, home in spring to thousands of seabirds. Its like a sea stack, only much longer. The legend here is that Chu Chulainn was trying to escape the advances of an old hag called Mal (short for Malcolm?) who had chased him amorously around the country. Arriving at this headland, our hero made the incredible leap onto the rock. Mal followed. Chu Chulainn leapt back. Mal leapt back too but didn't make it and fell to her death into the foaming ocean below. Where her head washed up was called Hag's Head and where her body was washed up was called Mal-bay, as in Miltown Malbay. (The story is also told with Dermot and Grainne as the two protagonists)

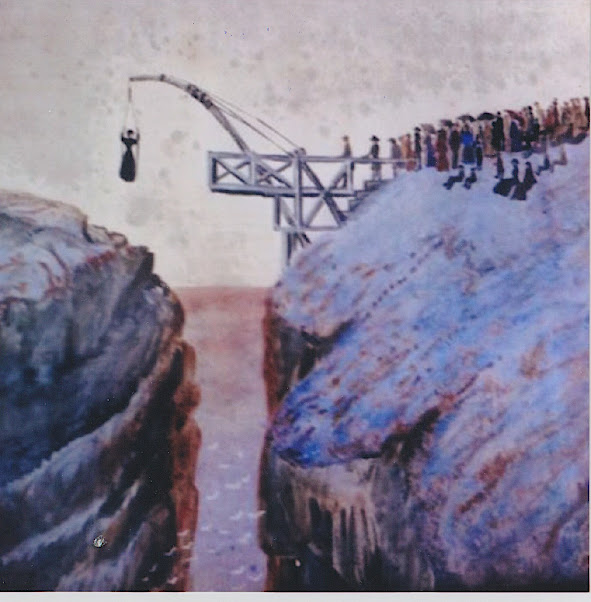

Now, believe that or not, there is an information poster in the lighthouse reading room that says that "In July 1893, a woman called Mrs. Griffin was the second person ever to make the crossing to "Sampson's Island," as it was called then, across Lovers Leap on the newly built contraption by Lighthouse keeper, Mr. Sampson."

The board was accompanied by a photograph of said contraption which, to me, looks suspiciously like a half a bridge. Maybe you took a long run and then leapt from the end of the bridge? Fair play to Mrs. Griffin, if that was the case.

Of course, I had to find out more and, back home, found a couple of sources online, predominately the Loop Head Peninsula Facebook page and a wonderful blog by an Aussie in Clare called Singersong. And the Lawrence photographic collection in the National Library

The photograph above in the library catalogue, actually names some of the people in the photograph

To the left, there are Elizabeth Sampson, daughter Alice, Mrs Simpson and Miss Simpson. By a wonderful piece of name management, William Sampson, lightkeeper, had married Elizabeth Simpson in 1885. Presumably then, the two Simpsons are Elizabeth's mother and sister.

There are actually two photographs in the Lawrence collection, taken relatively close in time. Two of the men in the two photographs are definitely the same. The one nearest the contraption is William Sampson, lightkeeper and contraption builder. The bearded man looks like he is one of the camera crew, possibly even Robert French himself. The third man is in profile in one photograph and in portrait in the other. He may be the same man - I can't tell. Possibly William or Elizabeth's father.

There is a sign on the rock. As far as I can tell it reads "Sampson Island / Landed" and then a date. The inference is that the first landing on the rock was not long after happening.

So who were the Sampsons? Well, William Parnell Sampson had been born in county Down around 1858, the son of a Royal Navy carpenter. The reason for the unusual middle name is uncertain, as the Uncrowned King of Ireland, Charles Stewart Parnell, would have only been twelve years old at the time. There is evidence that William joined the army as a young man but by 1885, when he married Elizabeth Simpson, he was a lightkeeper at the Queenstown (Cobh) pile light in Cork harbour. Elizabeth's father, John, possibly in the photographs above, was an army pensioner.

Due to the paucity of Irish Lights records in the 1800s, the best way of detailing William's career is through the births of his children. (This works with an unusual surname like Sampson but not with say, Ryan or Byrne) Thus we know that he was on the Fastnet when son William was born in 1887; he was on the Bull Rock when Alice (the girl in the photo) and Emily were born in 1889 and 1890 respectively; at Loop Head when Hugh (1891), Ada (1893) and John (1894) were born. The family were also in Blacksod (1897-1900); back on the Spit Bank in Queenstown for the 1901 census; and in Tarbert for the 1911 census. William later retired to Larne, where he died in 1936, aged about 77.

But what of Mrs. Griffin? Who was she and did she really do a death-defying long jump over the gap? Well, to answer the second question first, no, not quite. We are fortunate though to have a remarkable painting of the actual crossing:

It appears as though Mrs. Griffin grasped a hold of a trapeze, rather like standing up on a swing, and then the hoist swung around and landed her on the far side of the chasm. Not quite so death-defying as a leap of faith, but I wouldn't be over-eager to chance it meself, particularly in front of a large audience. I later found out that two of the steel bolts that affixed the contraption to the side of the cliff are still visible, as per the photo below on the Singersong blog As she rightly says, for God's sake, take care, if you visit and are trying to find them. One small slip and you end up like poor old Mal. Amy Griffin (she was born Amelia Griffin) was quite a remarkable lady. Born in Ennis around 1856, she spent her childhood between Dublin and Kilbaha (the last village before Loop Head). She was an avid diarist and later was well-known in the locality as a poet and a painter. She married Dr. John Griffin (yes, same surname), a widower of Kilkee, in 1883. (I had originally written Kilkeel, which was questioned very nicely. My bad!) She was roughly 27. He was 74. She was widowed three years later.

A political animal, gender reforms meant she was one of twelve Kilkee Town Commissioners elected in 1901. But she is best remembered as a poet and two of her poems commemorating West Clare tragedies are transcribed on a memorial at Kilbaha. The Five Pilots Poem details an 1873 disaster when five Kilbaha men were drowned trying to board a brig entering the Shannon; and The Grave of the Yellow Men concerns the washing up on the shore of eleven yellow-skinned bodies whose origins are to this day still a mystery. She died in Kilkee in 1910 aged 53.

As Amy was a painter, and the name of the painter of the scene is unknown, might it not be possible that Amy herself painted the picture?

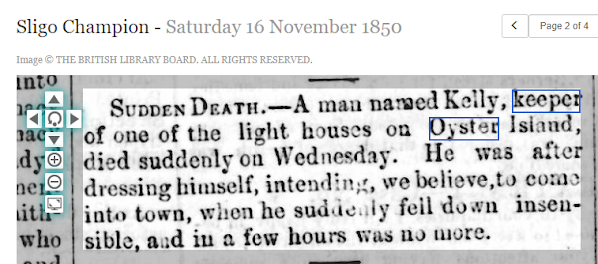

Finally a couple of contemporary newspaper clippings of the time. The 'well-known inhabitant' is of course Billy Sampson, who may have asked for the Times to omit his name in case the bigwigs in Irish Lights decided to transfer him to somewhere like Blacksod. It also dates the building of the contraption to 1893. There had been a bit of surmising about this on the Facebook page.

The Lighthouse Inn, Kilbaha in 2006 (now the Loop Head Lodge)

The

Grave of the Yellow Men

None knew from

whither those drowned men came,

Swept in by the

foaming tide.

So a grave was dug

without a name,

Where they slumber

side by side.

Their deeds are not

spoken above the clay,

They perished we

know not when.

Only a green mound

marks today,

The Grave of the

Yellow Men.

Even the wild wind

sings their dirge,

While the sea birds

in echo cry.

And eternally wet

by the briny surge,

Is the spot where

the strangers lie.

Benefiting for

those whose lives are dark,

And whose death was

full of pain,

But never recording

stone doth mark,

The Grave of the

Yellow Men.

Fond wives may have

wept through the dreary night,

For the husbands

they loved so well,

And at first faint

dawn of welcome light,

Arisen, their beads

to tell.

To hear the babes

as the brightly wake,

Has father come

home again?

Oh, hearts may have

longed they might only break,

On the Grave of the

Yellow Men.

We know they died

on the raging deep,

But they lived we

know not how.

Well their secret

those slumberers keep,

None will ever tell

it now.

But we know that

the name of each lost one there,

Has been graved by

his Maker’s pen.

Nor will He at last

have forgotten where

To seek for The Yellow

Men.