A blog about Irish Lighthouses past and present and other selected maritime beacons and buoys of interest. If anybody has any corrections or additional info on any post, please use the comment section or the email address on the right.

Thursday, November 24, 2022

Loop Head lightkeeper - a cautionary tale

Friday, November 18, 2022

Blackhead lighthouse, county Antrim

Saturday, November 12, 2022

Buoys oh Buoys

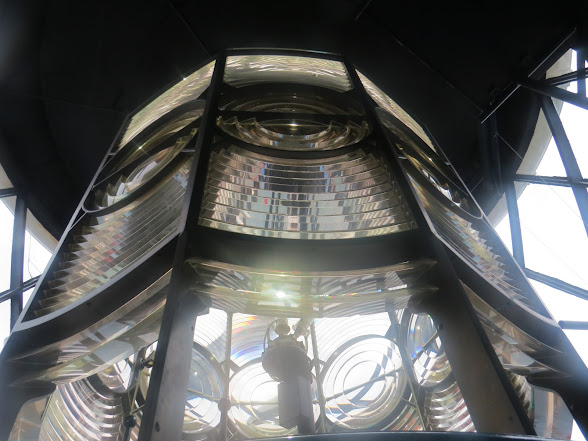

Photograph courtesy John McCarron

Thursday, November 10, 2022

As regards lighthouse animals, are these the GOAT?

Thursday, November 3, 2022

Fine art, poetry and music at Eagle Island in the 1870s and 1880s

The painting above is also by Richard Brydges Beechey and is entitled "Eagle Island, off Erris Head, W. Coast of Ireland," which is better but still too wordy. It was painted in 1885, ten years later. One suspects the driftwood (bottom left) was part of the Irish brigantine, Sligo, in the top picture, which seems to have been placed just where those two nasty rocks jut out.

Of course, it isn't easy marrying CB's words of a tranquil sea with Beechey's violent waves for which Eagle Island is renowned. It is also difficult imagining the cost of public liability insurance today for a cruise around an island notorious for bad weather but, as I have often maintained, the Victorians were completely mad.

And if that wasn't enough to convince you that Eagle Island, more than Florence or Milan or London was the artistic capital of the world in the 1870s, I give you a testimonial from Charles O'Brien, lightkeeper, of Eagle Island, who doubtless organised melodeon parties on the rock as part of his enlightened musical education policies in regard to the children of his fellow-keepers.

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)